“Watch out—beware of the yeast of the Pharisees and the yeast of Herod.”

One of my gifts is tearing into the text. I have spent a lifetime looking at the Word of God and learning to explore everything the text has to offer. I typically prefer a socio-rhetorical “textured” approach of exegesis, if you aren’t familiar with this term Vernon K. Robbins book, “Exploring the Texture of Texts” [1] or Fee and Stuart’s “How to read the Bible for all it’s worth” [2] are both great places to start.

Eisegesis and exegesis are two different styles of interpreting the Bible. “Eisegesis” lately has almost turned into a bad word within theology while “exegesis” has become the cool thing! There is a place for both.

Exegesis is a method of interpreting the Bible that focuses on drawing meaning from the text itself, using a succinct method of interpretation such as historical, cultural, and literary context to understand the author’s intended meaning and the mindset towards the intended audience. (That is the textured approach I describe above).

A good Eisegesis, on the other hand, is taking the text or Biblical subject matter (often topical), considering the exegesis of appropriate texts and applying a commentary or insight to the teaching based on one’s own ideas, beliefs, doctrines, and theology. Unfortunately, most Eisegesis is not “good” eisegesis as most commonly they forget to start with an exegesis – it can be a person’s commentary without due diligence to the text. I have often said when you take the TEXT out of its CONTEXT all you have left is a CON. The result is often simply making out the word of God to say whatever the person wants it to say or fits their agenda and is sometimes referred to as “proof-texting.”

While exegesis is considered the more academically valid approach to interpreting the Bible, eisegesis is valuable to bring an application to the audience in the present tense setting. In certain instances, the minister may need to make the text more potentially relevant to their congregation by drawing parallels between the biblical text and the current cultural, social, or (possibly) political environments and perspectives. (Based on the exegesis of the text, how does this subject or topic apply to us and our current environment.) This subject matter is debatable as most scholars have very little room for eisegesis and conversely some pastors have never truly learned to exegete the text but might be masters of eisegesis while walking a slippery line of possibly proof-texting.

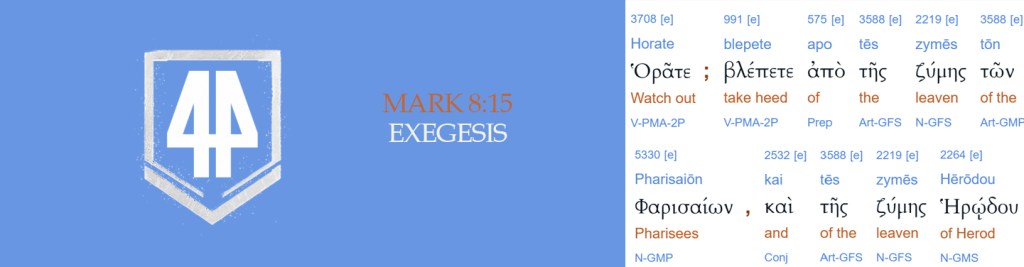

Every good exegesis starts with the original language.

+ Watch out is one word in Greek, which is horate or ‘orate in Greek. This is one situation where it helps to know a little Greek. When I read this, I first take note of the use of the root word ‘orate. It means “beware.” But what I first recognize (that you might not uncover in an interlinear) is that it isn’t a regularly used word to describe “beware”. Jesus could have used the most common word prosécho̱ which means watch, watch out, notice, look after, look out, or perhaps fylássomai apó, or na fovásai. In fact, if you were to just simply go to google and type in “what is the Greek word for beware” you wouldn’t find the word ‘orate at all. It was a very rare choice within the language and quite strategic. It’s a strong appeal for intense scrutiny. Jesus uses this term several times in a sense of extreme warning such as in Luke 12:15 to be on your guard. When a strong word is used it usually carries strong implications. So, I am going to be looking further in the verse to find these pointers. One more thing to note, the sentence starts out with the word, in Greek the first word often emphasizes the subject matter, it is a way of getting your mind to focus on what’s important or telling you what not to miss here. In some ways it resembles an exclamation point in English.

+ The next word is “take heed” which is the single word / verb blepó. This is similar to the first word and is the use of Hebraic reiteration. In other words, He isn’t just using ‘orate – the strongest word for beware, but then even reiterates the idea! This is a form of artistic emphasis. This is the same word used in Matthew 11:4 for hear “and see.” It is also used and translated by the NASB and most frequently in all capitals letters to show enunciation in Mark 8:18 “DO YOU NOT SEE?“ The emphasis of linking ‘orate with blepó is the strongest language found in the New Testament and comes right from the lips of Jesus. Do I have your attention yet?

+ The next word we come to is likely the heart of his message and in English we read the word “leaven.” In Greek the word is zumé. Jesus often uses words with multiple meanings and that is what is happening here. In the first century they didn’t have the medical understanding we have today. Bread was important to Jesus (bread of life, bread and water etc.). At every level people understood that leaven was used to make bread rise and often gave way to a better taste ( i.e. giving into something that felt good), the connotation was that it is simply part of most people’s lives (but took on some negative implication). Jews didn’t partake in “rising bread” during Passover – they didn’t use leaven. This was a commitment to being set apart and undefiled. You see leaven is actually yeast and yeasts are technically an infection. Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom. Yeast converts carbohydrates to carbon dioxide and alcohols through the process of fermentation. The products of this reaction have been used in baking and the production of alcoholic beverages for thousands of years. [3]

As an example of eisegesis, let me expound on a cultural dynamic to this text. In the first century when you got an infection it was serious. It could end up leading to a slow painful death. Life was pictured by bread but also by the blood. I won’t let your minds wonder too far but yeast infected the blood and they knew that they were familiar with that understanding and the words of Jesus to infer this. There is also a meaning to be found in the way that the leaven of bread or the bumps of an infection rise up on your skin. There could be an implication of alcohol too, that a little soon turns into too much and leads to sin.

As you can see, a good eisegesis should lead you full circle back to agreement of the exegesis of the text. You can see that here agreeing with my eisegesis as Strong’s suggests:

“2219 zýmē – leaven (yeast); (figuratively) the spreading influence of what is typically concealed (but still very dramatic). Leaven is generally a symbol of the spreading nature of evil but note the exception at Lk 13:20:21 (parallel Mt 13:32,33).” In the first century, infection often could lead to a slow grueling death that not only affected you but would require care givers to look after you. It was thought of as a selfish accusation of not caring about the ramifications of your actions. Alcoholism in the first century often took on the same selfish persona.

https://biblehub.com/greek/2219.htm [4]

I don’t want to get too sidetracked on unleavened bread, but as an example of continued eisegesis I also want you to completely understand the reasoning and implications. You will notice that a good eisegesis still takes into account the exegesis of other scriptures within the lens of your topic. The Israelites were to eat the Passover lamb “with unleavened bread” (Ex.12:8). They also were to remove all leaven from their homes and eat unleavened bread for an additional seven days: “On the first day you shall remove leaven from your hous-es. For whoever eats leavened bread from the first day until the seventh day, that person shall be cut off from Israel” (v. 15). Traditionally there is also a sense that he Jewish people “came out of the land of Egypt in haste” (Dt. 16:3) and had no time to wait for their bread to rise. So the Passover holiday commemorates the Exodus with unleavened bread. To be clear, unleavened bread is only avoided for these 8 days around Passover. But simply because God doesn’t forbid it the rest of the time didn’t mean that it was “good” or tov or recommended. There are different theological takes on this. Some would say it was “allowed” or “acceptable”, others would say that God set the “ideal” and that partaking of at any time was frowned on, while some arrive at everything in moderation. Interesting how this conversation ties very similarly into a modern discussion of Christians and alcohol.

In most cases, the eisegesis will result in a relevant modern cultural message very similar to the exegesis of the text to its original intended audience. In this case, however, you cut it, leaven is associated with sin. Jesus wanted His followers to be different. He wanted them to be holy. The apostle Paul wrote, “Do you not know that a little leaven leavens the whole lump?” (1 Cor. 5:6). A tiny bit of yeast can produce two large loaves of bread. Leaven permeates the other ingredients, begins to ferment, and expands. Sin is similar. It begins small, like a little germ or infection, then grows bigger and bigger. In many cases, it can totally overtake an individual. God required His people to eat unleavened bread for eight days to remind them that they were to be separate from the world, set apart from sin, debt, and transgression. God had redeemed them from bondage in Egypt and wants you to live redeemed and sanctified -free from the bondage of the world. This is the exodus motif we read of repeatedly in the Bible and is why Jesus sets the path for what is called a “New Exodus.” It was a continual (in your face every day) reminder that they were to be given solely to God and that their kingdom is that of Jesus not of the world.

Do you see the circular connection between a good exegesis and eisegesis?

+ Then we are told that the leaven picture connects to the “pharisees.” This is where your theology connects to the entire lens. What have you learned elsewhere in your exegesis? This is archetype language. An archetype is an example of something. Abraham is an archetype of great faith, Job righteousness, and here Jesus identifies the pharisees, a group that should be the best of Godly people because of their religious knowledge as actually being possibly the worst; or the archetypical example of people that personify sin. This is contranym language. They should be the most holy, yet by allowing their sin to take root and grow they have become the worst; people that claim God yet do not know Him. They were “puffed up” people. The were full of pride. Pharisee” is derived from the Aramaic term, peras (“to divide and separate”). This literally refers to a “separatist“; hence, a Pharisee was supposed to be someone “separated from sin“; but Jesus is actually saying they are the worst of the sinners, don’t let yourself slip into that kind of sin. According to Josephus [5] they numbered more than 6,000. They were bitter enemies of Jesus and his cause; and were in turn severely rebuked by him for their avarice, ambition, hollow reliance on outward works, and affectation of piety in order to gain notoriety: Matthew 3:7; Matthew 5:20; Matthew 7:29.

An important part of both exegesis and eisegesis is asking then, how do these connect and what can I take away and apply to myself?

To put it together – the text is as strongly as possible warning to not get prideful and puffed up like the pharisees because it infects the blood, makes you proud (not humble like Jesus) and infects the life (bread and blood) and leads to a slow grueling death that affects not only you but those around you. It is exactly the opposite of who you were created to be as an image bearer for a Jesus kingdom.

Lastly, we have Herod. This one is harder, you can’t just pull up an interlinear and find the answer -we actually have to think about it and possibly to some research (perhaps more eisegesis). What was Jesus saying by tying in Herod? Herod Antipas was the son of King Herod who executed all the children in Bethlehem as you might remember from the Christmas story timeline. He did this to find Jesus and put Him to death. Consider this for a minute. Herod was fanatical about power; he had his own children killed in order to preserve his throne. This Herod was the one who imprisoned John the Baptist. You probably remember that John spoke out against him because Herod stole his brother’s wife and was living in adultery. John called him out for the sin rising in his life that was generally kept secret “under the covers” or “in the darkness” we often say. But John exposed his private sin and brought it to the light of the public. What Jesus is saying is that Herod let leaven creep into his life and became a terrible person as a continual result (another archetype of the most sinful of people). This is a stark warning to not act on letting sin seep into the darker places of your life thinking that no one knows about them. God sees people for who they are from the inside. This becomes a very intelligent word play as the sexual ramifications also affect the blood which lead to life or death.

In the end the simple phrase speaks volumes. In Hebraic terms this is referred to as a technique that was later called remez. It was eloquent for rabbis in teaching to use part of a Scripture passage or an idiom in a discussion, assuming that their audience’s knowledge of the Bible would allow them to deduce for themselves the fuller meaning of the teaching. Jesus, who possessed a brilliant understanding of Scripture and strong teaching skills, used this method often.

Lastly, asking the hard questions is important. Have I been biased based on anything? Are there other considerations that I have left out? In this case, you may know that I don’t like politics! I don’t have alot of room for this thought but if I am truly going to be unbiased, I need to consider every aspect. In this case part of my exegesis and eisegesis is going to be phoning a friend. My good friend Steve Cassell is “in” the middle of the Christian political world. I asked him to comment on what the political ramifications might imply from this text today.

In our modern context, how would Jesus’ warning about the leaven of Herod be in view today? I acknowledge the tenuousness of this topic because of how polarizing and offensive any political commentary can be in today’s modern and delicate version of Christianity. Yet the weightiness of the Master’s warning cannot be neglected by us who hold vigorously to the Truth as a remnant people.

In Jesus’ day, Herod also represented the chief political figure of the established governmental system that affected every person’s life. Politics touches us all whether we want it or not. Even within the Jewish system, there was a large segment of confessing ‘Herodians’ (Mk 3:6, 12:13, Mt 22:16) who were those who believed that part of the spiritual ‘reformation’ of their culture was to be done through supporting political systems. How parallel for progressives today. One of the present-day dangers of the ‘leaven of Herod’ is those wrongly, yet likely well-intended, believers who fervently adhere to thinking that a righteous government will somehow bear the fruit of righteous people. That potential is reserved ONLY for the King and His Kingdom to produce. It is a subtle trap that has caught and bloated vast swaths of Americans today and it is in danger of leavening the whole lump of the Body of Christ which is the loaf that was baked in the fire and oil of the atonement and Holy Spirit.

-Dr. Steve Cassell

This is just an example of a very simple text but is serves to give you a better idea of what the text should mean to us today. It also may give you an idea of what you should be getting out of a text and how much room you have for application to yourself or current environment.

The phrase Jesus quotes is very creatively crafted to staunchly warn about seeking self-glory publicly and allowing and acting on private sins, both lead to the gradual rotten path of death.

- Vernon K. Robbins. Exploring the Texture of Texts: A Guide to Socio-Rhetorical Interpretation. Valley Forge, Pennsylvania: Trinity Press International, 1996.

- Gordon Fee and Douglas Stuart, How to Read the Bible for All It’s Worth (Zondervan, 1981; 2014 reprint)

- Legras JL, Merdinoglu D, Cornuet JM, Karst F (2007). “Bread, beer and wine: Saccharomyces cerevisiae diversity reflects human history”

- https://biblehub.com/greek/2219.htm

- Josephus (Antiquities 17, 2, 4)