The question of whether Adam and Eve spoke Hebrew in the Eden narrative has persisted within both popular and academic discussions of early Genesis. While the biblical text depicts the first humans engaging in meaningful, structured speech, it does not explicitly identify the linguistic form of that speech. This study examines the question from a philological, literary, and theological perspective, arguing that while Hebrew wordplay in Genesis is theologically significant, it does not necessitate the conclusion that Hebrew was the primordial human language.

The Genesis narrative presents humanity as linguistically capable from the outset. In Genesis 2:19–20, Adam exercises dominion through naming the animals. Naming in the Ancient Near Eastern context is not merely descriptive but also ontological, reflecting authority and classification.

Genesis 11:1 later affirms that “the whole earth had one language and the same words,” indicating a primordial linguistic unity prior to the Babel event (Genesis 11:7–9). However, the text remains silent regarding the identity of this language.

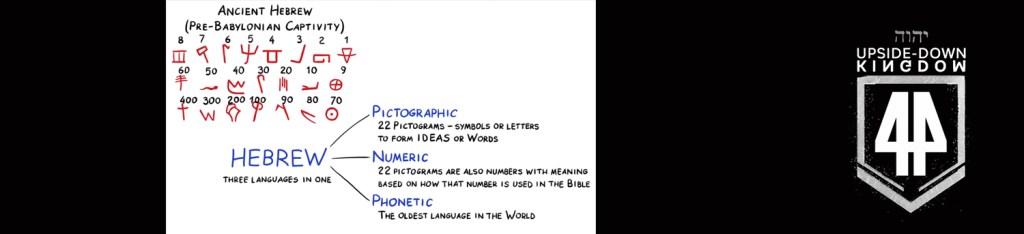

One of the most common proposals is that Hebrew was the original language of humanity. This argument is typically grounded in the semantic transparency of key names in Genesis: Adam is connected to ground, and Eve to life. These connections create compelling literary and theological wordplay within the Hebrew text. However, the Book of Genesis was composed and transmitted in Hebrew, making it methodologically plausible that the inspired author employed Hebrew lexical connections to communicate theological truths to a Hebrew-speaking audience.

Alternative models include the possibility of a lost proto-human language, a unique Edenic language, or narrative accommodation where the Genesis author presents primordial events through the linguistic and conceptual framework of Hebrew.

The biblical text affirms that Adam and Eve used meaningful language, early humanity shared a unified language, and the specific identity of that language is not disclosed. The Hebrew hypothesis remains a reasonable inference but not an exegetical conclusion.

Discussion Questions

To what extent should Hebrew wordplay in Genesis be understood as literary theology rather than historical linguistic evidence?

How does the concept of naming in Genesis 2 reflect Ancient Near Eastern understandings of authority and ontology?

What hermeneutical risks arise when later linguistic forms are retrojected into primeval history?

How does Genesis 11 (Babel) inform our understanding of linguistic diversity in relation to divine sovereignty?

In what ways does the presence of language in Eden contribute to a doctrine of the image of God?

Bibliography

Alter, Robert. Genesis: Translation and Commentary. W.W. Norton, 1996.

Barr, James. The Semantics of Biblical Language. Oxford University Press, 1961.

Cassuto, Umberto. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Magnes Press, 1961.

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1–17. Eerdmans, 1990.

Heiser, Michael S. The Unseen Realm. Lexham Press, 2015.

Kidner, Derek. Genesis: An Introduction and Commentary. IVP, 1967.

Sailhamer, John H. The Pentateuch as Narrative. Zondervan, 1992.

Walton, John H. The Lost World of Genesis One. IVP Academic, 2009.

Wenham, Gordon J. Genesis 1–15. Word Biblical Commentary, 1987.