Introduction

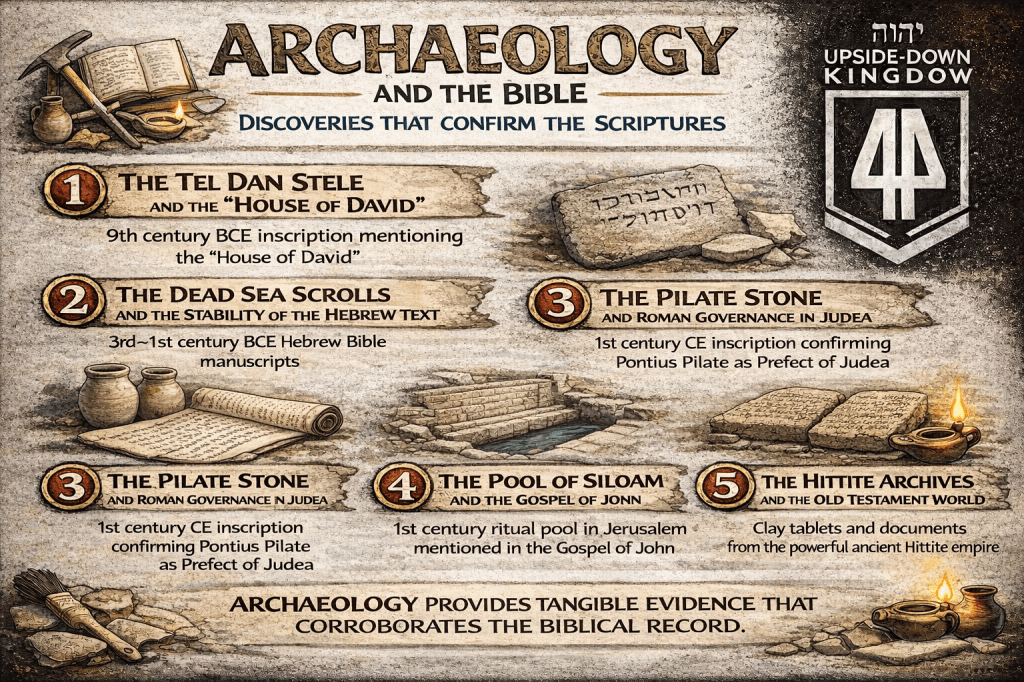

Biblical archaeology does not “prove” the theological claims of Scripture in a strict philosophical sense; however, it does provide a material context that can either corroborate or challenge the historical plausibility of the biblical narrative. Over the past century and a half, a series of major archaeological discoveries have significantly strengthened confidence in the Bible’s historical setting, literary transmission, and cultural coherence. This article surveys five of the most widely discussed discoveries and explores their implications for textual apprehension—that is, how readers understand, interpret, and situate the biblical text in its historical world.

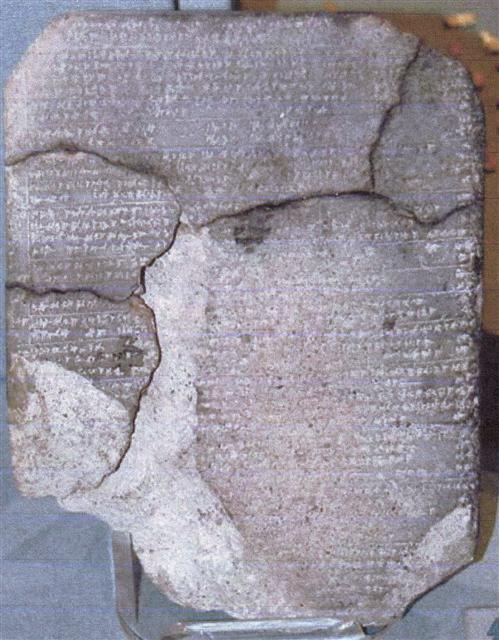

1. The Tel Dan Stele and the “House of David”

Discovered in 1993–1994 at Tel Dan in northern Israel, the Tel Dan Stele is an Aramaic inscription dating to the 9th century BCE. It contains the phrase bytdwd (“House of David”), which most scholars interpret as a dynastic reference to King David.

Significance

Prior to this discovery, some minimalist scholars argued that David was a legendary or composite figure. The Tel Dan Stele provides the earliest extra-biblical reference to David’s royal line, lending historical credibility to the Davidic monarchy described in 1–2 Samuel and Kings.

Implications for Textual Apprehension

The stele reinforces that the biblical authors were not inventing a fictional dynastic origin, but were engaging a known political reality. This strengthens the plausibility of the historical framework within which the theological claims of covenant (2 Samuel 7) are embedded.

2. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Stability of the Hebrew Text

Discovered between 1947 and 1956 near Qumran, the Dead Sea Scrolls include manuscripts of nearly every book of the Hebrew Bible, some dating as early as the 3rd century BCE.

Significance

Comparison between the Great Isaiah Scroll and later Masoretic manuscripts (c. 10th century CE) shows remarkable textual stability across nearly a millennium of transmission.

Implications for Textual Apprehension

The scrolls dramatically reinforce the reliability of the textual tradition behind modern Old Testament translations. They also demonstrate that the textual communities of Second Temple Judaism transmitted Scripture with extraordinary care, supporting the assumption that the biblical text used in theological argumentation today is substantially consistent with ancient forms.

3. The Pilate Stone and Roman Governance in Judea

In 1961, excavations at Caesarea Maritima uncovered a limestone block bearing a Latin inscription that includes the name Pontius Pilatus, the Roman prefect of Judea referenced in the Gospels.

Significance

The inscription confirms the historical existence and title of Pontius Pilate, validating the Gospel accounts (e.g., Matthew 27; John 19) within a known Roman administrative structure.

Implications for Textual Apprehension

The Gospels demonstrate familiarity with Roman provincial governance, titles, and political realities. The Pilate Stone situates the crucifixion narrative within a verifiable administrative context, underscoring that the passion accounts are anchored in real historical governance rather than later legendary development.

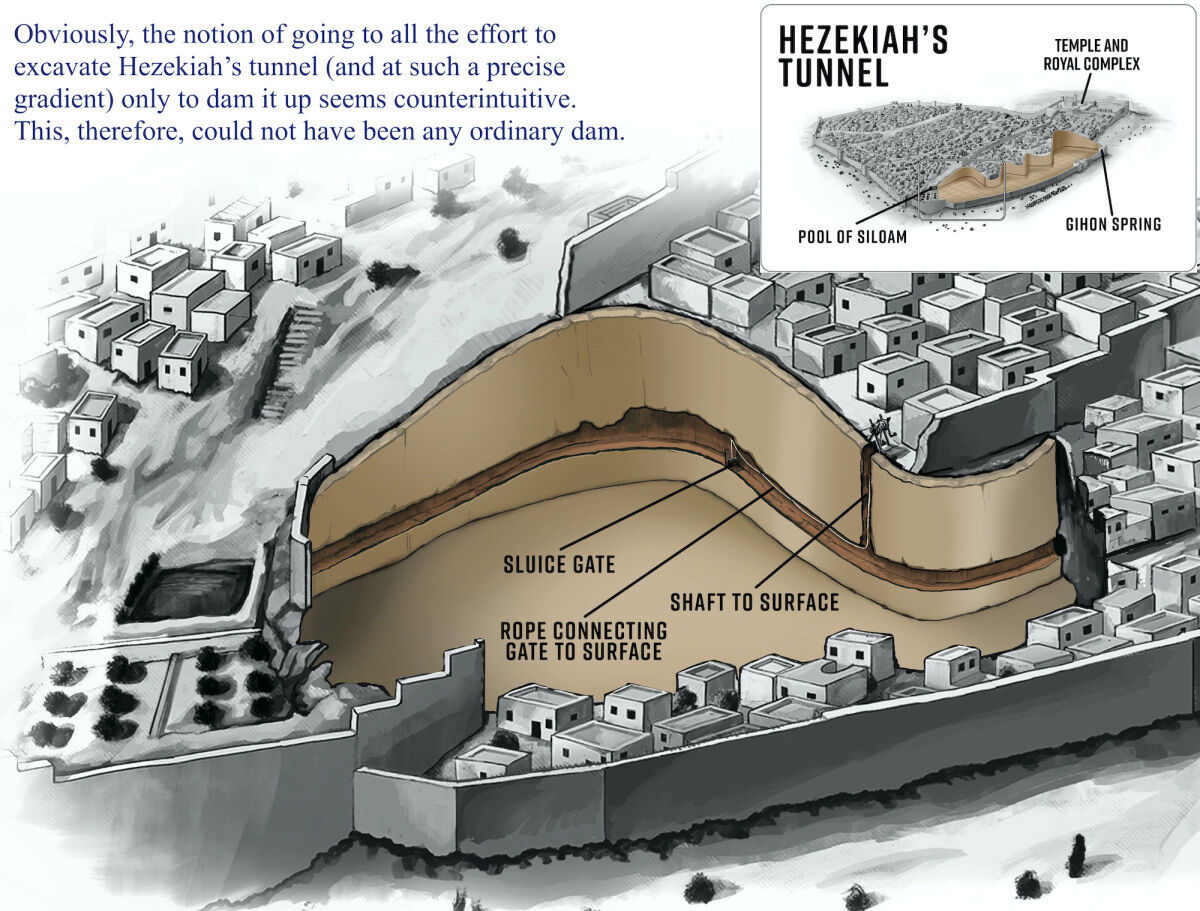

4. The Pool of Siloam and the Gospel of John

In 2004, archaeologists uncovered the Second Temple–period Pool of Siloam in Jerusalem, referenced in John 9 as the site where Jesus healed a blind man.

Significance

The discovery confirmed the pool’s size, location, and function as a major ritual immersion site in first-century Jerusalem.

Implications for Textual Apprehension

The Gospel of John is sometimes accused of being theologically rich but historically imprecise. However, the accurate topographical detail regarding the Pool of Siloam strengthens confidence that the Johannine narrative reflects genuine knowledge of Jerusalem’s geography prior to its destruction in 70 CE.

5. The Hittite Archives and the Old Testament World

Nineteenth-century critics doubted the biblical references to the Hittites (e.g., Genesis 23; 2 Kings 7), considering them fictional. Excavations at Hattusa (modern Boğazköy, Turkey) uncovered a vast Hittite empire with extensive archives.

Significance

Thousands of cuneiform tablets revealed a sophisticated political culture, including covenant treaty structures strikingly similar to biblical covenant forms (e.g., Deuteronomy).

Implications for Textual Apprehension

The discovery reframes the Old Testament covenant texts as belonging to a recognizable Ancient Near Eastern literary genre. This supports readings of Deuteronomy and related texts as historically situated covenant documents rather than later theological inventions.

Conclusion

These five discoveries do not “prove” the theological truth claims of Scripture; however, they demonstrate that the Bible emerges from a historically grounded world that is increasingly accessible through archaeology. For biblical interpreters, this matters deeply. Theological claims in Scripture are not abstract philosophical propositions detached from history; they are embedded in real people, places, languages, and political structures. Archaeology, therefore, strengthens the plausibility of the biblical narrative and refines our interpretive lens, enabling a more historically responsible reading of the text.

Discussion Questions

- In what ways does archaeological corroboration strengthen (or fail to strengthen) theological confidence in Scripture?

- How should interpreters balance archaeological data with literary and theological analysis when reading biblical narratives?

- Does the Tel Dan Stele definitively prove the historical David, or does it simply make his existence more plausible? Why does this distinction matter?

- What does the textual stability demonstrated by the Dead Sea Scrolls imply for modern debates about biblical authority and inspiration?

- How do discoveries such as the Hittite treaties reshape our understanding of covenant language in Deuteronomy and the broader Old Testament?

Selected Bibliography

Archaeology and the Bible

- Dever, William G. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001.

- Kitchen, K. A. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

- Hoffmeier, James K. The Archaeology of the Bible. Oxford: Lion, 2019.

- Mazar, Amihai. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, Vol. 1. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

Specific Discoveries

- Biran, Avraham, and Joseph Naveh. “The Tel Dan Inscription.” Israel Exploration Journal 45 (1995): 1–18.

- Cross, Frank Moore. The Ancient Library of Qumran and Modern Biblical Studies. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1995.

- Taylor, Joan E. The Essenes, the Scrolls, and the Dead Sea. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Bond, Helen K. Pontius Pilate in History and Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Reich, Ronny, and Eli Shukron. “The Pool of Siloam in Jerusalem.” Biblical Archaeology Review 31.5 (2005): 16–23.

- Beckman, Gary. Hittite Diplomatic Texts. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1999.

Textual Criticism and Transmission

- Tov, Emanuel. Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012.

- Ulrich, Eugene. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Developmental Composition of the Bible. Leiden: Brill, 2015.