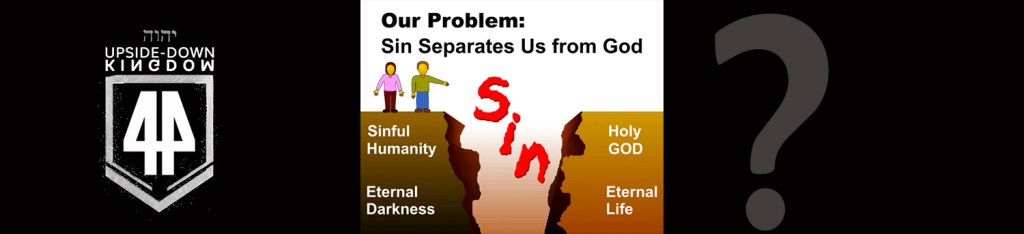

When I was in High school attending a rather large evangelical free church, we had some missionaries come in to train us on street evangelism. The idea was to memorize a step plan for salvation that we could easily regurgitate on the streets. The core of it was based on convincing someone that according to Adams sin we had been separated from God and that only by professing with our mouth and praying the sinner’s prayer could we escape eternal torment and damnation. As there is arguably some truth to that statement, the presentation not only created some terrible theological implications of the gospel message (both to those presenting and those being presented to) but also wasn’t necessarily the best Biblical framework. Of course, as “good” kids we all just went along with it, at least initially. As you can imagine this led to some really awkward conversations in the street and left several students wondering if this is what Christianity is all about whether they really wanted to be part of it. The following year a different but similar group came essentially “training” us to try to do the same thing evangelizing our hometown. But then something happened, this time (likely based on their previous poor experience) several of the students started to transparently challenge the process. I remember it almost as if it was the enslaved rebels of Star Wars questioning the empirical ideals. Questions like, “where does it actually say this in the Bible?” and “Do you really think this is the action that the text had in mind when it was written?” Another student said, “I don’t think I want anything to do with a plan like this, I didn’t come to Jesus to force my friends into submission.” I could go on and on. The training group couldn’t really answer them with any kind of logical explanations, and I was quite disheartened by the whole thing. The night resulted in half the youth group leaving early bailing on street evangelism to go out for ice cream; while the other half (some likely afraid of their parent’s repercussions if they left) continued with the group to evangelize. I am sure there was a small percentage of the “good” kids that convinced themselves this was what good Christian kids should do. I was also skeptical of Billy Graham “crusades” as a kid. And before I continue, I want to say that even though I still don’t entirely agree with these crusades and this kind of step plan evangelistic plans I do believe God uses it in powerful ways. I know many that came to faith this way and then over the course of time found a better theology. But my heart desires to say, let’s start with a better theology!

This youth group interaction was a monumental occurrence in my life that made me start questioning why Christians do what they do and whether the Bible actually said things like the church traditionally claimed. Instead of driving me away from Christianity, as some thought questioning the faith would do, it drove me towards a lifelong beautiful “expedition” towards understanding the incredible word of God and His nature. I don’t know of anyone who has had such joy in the journey. This is my love language, and I pray that it becomes yours.

UNDERSTANDING THE PROBLEMS WITH FRAMING SEPERATION FROM GOD THEOLOGY

The central question for your consideration is does the Bible actually say and teach what we have so often regurgitated that “sin has separated us from God?” I will start by saying any time you here a doctrine and you can’t find one verse that clearly states what the doctrine is attempting to “make the gospel say,” the best advice might be to run. If the intent of God was to give us some crafty 4 step plan of salvation wouldn’t that be clearly laid out somewhere in the text? Yet in the “ROMANS ROAD” plan of salvation we have to jump all over Romans back and forth to try to understand the so called laid out plan. Similarly, if a doctrine states something simply in one sentence such as “sin separates us from God” shouldn’t the Bible also state it similarly if it is true? That would make sense. Yet something as engrained in our head such as the statement, “sin separates us from God” doesn’t ever seem to be stated that way anywhere in the text. We deduce it. That doesn’t make it wrong or untrue, it just raises some hermeneutic red flags that should cause you the need or desire to examine it.

What verses then tell us that we are separated from God by Sin?1 Here are the best ones coming straight from those that hold this type of framework:

- Isaiah 59:2: “But your iniquities have made a separation between you and your God, and your sins have hidden his face from you so that he does not hear.”

- Romans 3:23: “For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.”

- Romans 6:23: “For the wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Are there others? Well, if you think these are a stretch, the others that people claim support separation you’re going to have an even harder time with. These are the closest verses that the Bible has that state we are separated from God by our sin. If you google the question the first link will be “100 verses by open Bible Info”. I will say that almost none of them actually state we are separated from God2, but such a simple search certainly shows that someone thinks or has been traditionally conditioned to tell us that.3

The only verse above that actually comes close to simply stating that sin has separated us from God is Isaiah 59:2. At first reading I can see this, however when you start applying textures of interpretation you see the verse differently. Basic laws of any hermeneutic design say, don’t ever make a doctrine off of one verse. In other words, if there is only one verse that seems to say something that can’t be found elsewhere in the pages of the Bible it likely doesn’t say what you mean what you think. If it did there would be supporting verses. SO then theologically you should be asking the question, if this verse seems to say this, but there isn’t another verse that says it, could there be a different meaning for this text? This kind of thinking leads to a better or more faithful interpretation and overall agreement in your theological lens. John Walton interprets Isaiah 59 as highlighting the necessity of a savior due to humanity’s iniquities and moral failures, yep, we need that!4 The Hebrew word used here that is interpreted as the English word “separated” is בָּדל (badal.) It is the same word used in Genesis one in the creation narrative used to describe the separation of the light, and water, day and night. Notice in these cases it isn’t a chasm that separates those things, and it is part of God’s order. In fact, the truth is that it is opposite to that way of thinking, day touches night beautifully. It is the most beautiful part of the day that we call sunrise and sunset. Where the land meets water is a beach! We all LOVE the beach. We want to dwell in beaches. We vacation on beaches. Do you see my point? To frame this word as division or a chasm that can’t be overcome isn’t Biblical. Sometimes beauty comes when the peace meets the chaos and that is often where God dwells in scripture. The Biblical picture is actually a “slice of heaven”, the most beautiful thing the world has seen. CS Lewis spent a great deal of time dwelling on this concept.5 Do you see what I am saying? Badal also is a form of setting something apart. You know the other Hebrew word that is used to say that? Kadosh – Holy. The context of Isaiah 59 is actually a word play in the form of a contranym. So yes, in one sense God is holy and sin is the opposite of Holiness, but God isn’t separated from us by that, He actually dwells close to it. The other problem with framing God so far away is that it is giving sin way too much power over you. I am not willing to give sin that kind of leverage or title in my life. God finds people in some of the darkest places. When you run away you think you are far from Him, but the Biblical truth is that God is right there for you. If you truly believe in the omnipresent of God than you have to take this theological perspective. To say there is a chasm between a person sinning and God doesn’t agree with the doctrine of omnipresence.

Furthermore, Isaiah 56 is a prophetic indictment to a people immersed in injustice, oppression, and violence. The “separation” here isn’t God walking away. It’s people who have closed their ears to God’s voice. It’s spiritual disconnection, not divine abandonment. There’s a difference between feeling distant from God and God actually being distant. God never leaves.6

Secondly, once we give our life to Jesus, sin doesn’t simply disappear. According to most plans of salvation logically that is what would make sense. If we are separated by God and we say the magic words than sin is no longer in our lives (the chasm would logically be bridged never to be empty again) but if sin truly separates, then it creates a theology that logically would mean that we would continually be in need of repetitive salvation prayers to bridge this gap over and over. We know that isn’t the case. It creates a poor theological framework. What is true is that we can make a heart and mind choice to live for Him and even though we are still in part of the earthly physical world we are free from the endearing result of sin which is death both in the physical life and eternally. That is grace. To actually believe in this great chasm, minimizes or does away with a Biblical concept of covenant grace. So, to frame sin as a separation from God logically and ontologically doesn’t make sense or follow the premise of the biblical story of God’s redemption of us. It misses the mark.

Furthermore, saying that sin has separated us from God frames the character of God in a way that doesn’t agree with the Bible. It leads us to thinks that from birth we naturally were being judged by the sin of those before us. Yet the Bible is clear that we are only responsible before the Lord for our own actions and not the actions of others. Yes, we are affected by others (perhaps even for generations) but that is slightly different. Affected and responsibility or having to earn something as a result of someone else’s past are different issues. This gets more into the original sin conversation than it does sin separation; but the two are certainly connected. If you haven’t watched or listened to the x44 series on original sin you should do that. Saying that we are always separated from God by sin assumes that when we “sin” God must turn his face or step away from us. That is not true. The overarching message of the Bible is that God does not leave us or forsake us. I wrote an article on this. Do you believe the nature of God gets angry and wrathful when you sin. Do you think God wants to smite you because you sin? That sounds monstrous doesn’t it, yet many peoples theology believes that. Yet God’s love for us couldn’t be more opposite of thinking that way. When we sin, God more than anything, grieves for us and wants to draw us closer to Him into His hand of providence. When we continue to sin God will eventually open his hand of protection and allow us to reap what we have sown. This is actually a more Biblical definition of wrath. We get what we had coming, God no longer protects. (Israel in exile is the archetypical picture of this, but God has always desired and welcomed them back with open arms, thus the prodigal son story and many more. There is no separation or barrier from God’s perspective.) When we think that God is separated from us by sin, we begin to believe that God loves us when we do good and leaves us when we don’t. Or perhaps we think that when we are in devotion to Him, He blesses us and when we are separated by sin He is done with us and can no longer use us for the kingdom. Those in the book of Job asked this question as a retribution principle and God was clear to answer at the end of the story that that is not His character. We have a series on that too. I am glad that isn’t the case. No one would have ever been used by God. Does God just leave us the second we screw up?

DOES SEPARATION OF GOD CHANGE AT THE CROSS?

This is a great question. If you are following along and thinking through the texts, you might realize that in the Old Covenant there seem to be examples of separation from God even though the text never really says it so simply. (As I previously made the point, it could be deduced from the text.) Romans 8 seems to support a notion that in the Old Covenant before the cross we were separated from God. That could be why the cloud came and went from Israel’s trail. It could also show the veil between the holy of holies and the need for a priest. But then when Christ comes as our once and for all great high priest and the veil is torn at the cross, we become the temple of the holy spirit to which the separation is broken. In this sense there MIGHT have been a separation between God and the people in the Old Testament but Jesus (not necessarily the cross itself) removed any sense of being separated. The only problem with holding a view that there was separation in the Old Testament is that the text never actually says it. If the text really intended us to take away that notion wouldn’t one of the 39 books clearly state that? Yet they don’t, it has to be deduced which then makes it a theology of humankind. That should always be problematic to your theology and possibly a dangerous place to dwell. Another great question that then follows suite would be, “Is there a separation for the unbeliever?” I don’t think so. If you take the view that in the OT there was a separation between God and humanity it would be with everyone, not just unbelievers. The cloud and the veil support that theology. If that foreshadows the NT then it would take on the same ideology. Neither believer nor unbeliever are separated then. They are all close to God, God is never far off. This may sound different than what you have always been told but there isn’t anything that would disagree with it; in fact, it takes on a far better lens of agreement within all the texts. I can’t think of one verse that would actually make this a difficult view to hold.

PERHAPS IT SEEMS LIKE THERE IS A SEPARATION BY SIN

Even though the Bible doesn’t seem to have the framework or state specifically that we are separated from God by sin wouldn’t that make sense. We have certainly always been told that -right? But since the Bible doesn’t say it, we would be left to deduce it. Is that faithful hermeneutics? Well, it can be, if you believe in systematic theology, you are already doing that sort of thing regularly. But Biblical theology questions those practices. In one sense it seems to follow logic that in a relationship if one side falls out of love or becomes distanced you might say they feel are even separated. We say that in broken marriages that grow apart all the time without micro analyzing it. But that doesn’t work biblically with God as one side of the relationship. We are told and shown this multiple times in the Bible. Jesus is the bride of Christ and even though the groom (sometimes viewed as Israel in the OT) was unfaithful, the bride remains completely faithful and therefore is not separated. The separation came from Israel creating a reason to be distanced but God Himself still never leaves or forsakes them in covenant love. Some would say God divorces Israel but that leaves some deep theological problems that need to be sorted if you go that way. The more accurate Biblical mosaic and unending motif of redemption is that despite the unfaithfulness of Israel God is near with open arms. To this design, even though someone distances themselves from God, (and in our human broken relationships) the same is not true of the character of God. God never distances himself from the lost, the divergent saved, the broken, the lost, or the unfaithful… God is always near (which is what the doctrine of omnipresence means, which is also a theology of humanity as long as we are making the statement.) It is important to have consistent theology. I have said many times that the reformed perspective of believing God is omnipresent and also believing that we can be separated from God doesn’t follow a logical pattern. The two views are at odds; they can’t both hold true. If you feel or sense that God is far away or you have severed your relationship, that is what you feel, but the reality and major thematic covenantal truth is that God hasn’t left you. This is true as a believer or unbeliever. God is always near; there is not a chasm between you and God.

UNDERSTANDING THE BIBLICAL TRUTH AND THE BETTER THEOLOGY

The Bible never once states that we are separated from God by sin, but it states over and over that nothing can separate us from God. And Jesus solidifies this regularly if there were any doubt.

Romans 8:38-39: “For I am sure that neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Something tells me you have sang loud “NOTHING CAN SEPRATE US” in the Your Love Never Fails song by Chris Quilala of Jesus Culture. Remember that? We sing it so confidently but then believe sin has formed a chasm? How does that work? You can’t sing a song like this and still theologically think that way.

Some say God can’t be in the presence of Evil. That isn’t true either. God clearly sees evil. He is involved, engaged, and working redemption in real time and space. The idea that God literally can’t be near sin is a misreading of the text, and a dangerous concept or doctrine.7

Jesus makes all things clear

Jesus shows us that God wasn’t separated from the sinful, that His heart was moved towards a deeper connection with those in sin than perhaps anyone else. Think about the relationship that Christ had with those in sin. How can you be separated and be in deep relationship at the same time? You can’t. Those two things are opposites. Yet Jesus had deep relationships and was NOT separated by sin to those dwelling in it. He drew a line on the ground for the woman in adultery turning back those who took offense, He touched and healed the unclean before they claimed any relationship with the father. He loved them before they had any semblance of knowing Him. He routinely shared a table with sinners and invited them to be in His sacred space. In other words, he didn’t build chasms between Himself and the sinful, rather He walked hand and hand with them shepherding them to Him. He entreated those that were immersed even drowning in their sin. That doesn’t sound like a cliff of separation to me. It sounds the opposite. It sounds and looks like relational love.

“Come to me, all who are weary and burdened…” (Matt. 11:28)

And when Jesus went to the cross, He entered fully into the consequence and depth of human sin, not to separate us from God, but to reveal how far God was willing to go to stay with us.8

CONSIDERING SIN

This article isn’t meant to diminish sin. Sin is the opposite of God, but as I have made the case isn’t impenetrable. Sin is infectious, it hurts, it cuts, it wounds, it severs, it destroys and requires spiritual healing. Make no doubt there. Continually giving into sin is the road to death both physically in this life now and also to come in an eschatological sense (already not yet). Sin masks our identity in Christ and creates worldly thoughts of shame, pride, fear, insecurity, hurt, doubt, trauma, and so much more. Sin hurts not only you but those in relationship and covenant with you. Sin can severe your ability to walk in the spiritual prosperity that God has for you. Sin inhibits the freedom that God gives. Sin is the opposite of the peace that God manifests in us. Jesus came to take away the sin of the world. I am in no way diminishing the effects of sin on this world.

Dr. Matt and I are writing a book on this, so I am going to keep the more theological section here brief, but I also feel like it needs to be shown in this article. The effect of Jesus’s death concerning humanity’s sins in 1 John (specifically but also every other reference) is to cleanse (kathatizo), or to remove (airo) sin, not to appease or satisfy. Thus, Jesus’ death as an “atoning sacrifice” functions as an expiation of sin and not the propitiation of God. This is exactly what is happening in the Day of Atonement, and it is the image John is using in the entirety of 1 John. There is not one image of God needing to be appeased in 1 John to forgive sin or cleanse.

What does “for our sins” mean? “For” can have many meanings. But Greek is specific whereas English is not. There are 4 words with 4 distinct meanings (with some minor overlap) in Greek for “for”:

- Anti: this for that (substitution or exchange)

- Eye for (anti) an eye, tooth for (anti) a tooth (Matt 5:38)

- “Do not repay anyone evil [in exchange] for (anti) evil” (Rom 12:17)

- Dia: Because of or on account of; from

- one agent acting against another agent or on behalf of another

- Peri: Concerning, about (sometimes overlaps with Dia)

- Conveying general information about something

- Huper: in some entity’s interest: for, on behalf of, for the sake of,

- the moving cause or reason: because of, for the sake of, for.

In 1 John 4:10 and 2:2 we see peri being used for “for”, besides Mark 10:45 (anti “this for that”- substitution or exchange)9 all of the other New Testament uses of “died for us”, “died for me”, and “died for our sins” and its cognates are huper -about a benefit, or as the Creed above said, “on our behalf”.10 I’m not saying that Jesus did not do something in our place (although I would be careful with using the term substitution doctrinally) but he did this on our behalf- for a benefit or to rescue us (but not from the Father).

Those 3 verses (Romans 3:25, 1 John 2:2, 1 John 4:10) are all of the references to “propitiation” in the NT. Hebrews 2:17 also uses a variation of this word and in context is about what the high priest does with the purification offering on the Day of Atonement. We’ve seen that all these mean expiations or show Jesus as the “mercy seat” when interpreted in the proper context of the Day of Atonement.

We do not see that the scapegoat or the purification offering had to be killed to propitiate God’s wrath. To interpret these in this way is going beyond the text and meaning of the Day of Atonement shadow. In other word’s framing the text that was is reading into it, it isn’t a faithful hermeneutic. The primary question about the Day of Atonement goats is whether God is being acted upon (changed?) or is sin being acted upon. As we saw with expiation, sin is the force being acted upon. But with propitiation, God is being acted upon. Yet, the noun’s use in the New Testament is about Jesus being the place where we connect with God because of his High Priestly and expiating function. This makes sense of Paul’s most popular phrase for salvation: “In Him”- Jesus is where (the place- Mercy Seat) we meet with God.

There are plenty of other corresponding verses that all agree with this methodology such as Leviticus 16; Romans 3:21-26, 1 John 2:2, 1 John 4:10; Heb 13:11-12; Matt 27:28-31; Heb 9:14-28; Heb 10:8-17; 1 John 3:5-8; John 1:29; Col 2:14; 2 Cor 5:21.

HOW DOES THIS AFFECT YOU?

If you believe sin separates you from God, then every time you fall short or miss the mark, you’ll think or believe that God’s love has left or betrayed you or has turned His face from you. That is such a poor image of God’s character and against everything the Bible says about His great redemption story. It is counter to almost every thematic motif in the Bible. Have you been harboring the lie that keeps you from experiencing what God wants most for you? Are you wallowing in your mess because you haven’t claimed redemption? God is always with you.

God’s grace for your sin is stronger than your worst nightmare or anything the world can dish out.

CONCLUSION11

Jesus didn’t come to make God love us.

He came to show us that God already did.

Sin is real. It has consequences. It can numb us, isolate us, distort our vision.

But it can’t separate us from God.

The cross is not a bridge to a distant God.

It’s the place where God meets us in the depths of our brokenness

And says, “I’m not going anywhere.”

Jesus is not your lifeline back to God.

Jesus is God – reaching, rescuing, embracing.

Always has been.

Always will be.

- https://www.gotquestions.org/plan-of-salvation.html ↩︎

- https://bible.org/article/gods-plan-salvation ↩︎

- https://www.openbible.info/topics/sin_separates_us_from_god ↩︎

- https://bible.ca/ef/expository-isaiah-59.htm ↩︎

- Carpenter, Humphrey (2006) [1978]. The Inklings of Oxford: C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Their Friends. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-774869-3. ↩︎

- https://pauldazet.substack.com/p/sin-doesnt-separate-us-from-god ↩︎

- IBID ↩︎

- IBID ↩︎

- In the image of the Exodus there was actually no substitution or exchange but that Jesus’ life was costly and his death and blood saves us from Death. Also see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRSqtE13v5k for a full word study on “For us” and all its uses in the NT. ↩︎

- Some of the most prominent sacrificial “For Us” verses in the NT that use huper (not anti): Rom 5:6-8; 1 Cor 15:3-5; 2 Cor 15:14-15; Gal 1:3-4; Gal 2:20; Eph 5:1-2; 1 Thes 5: 9-10; Titus 2:11-14; Heb 2:9-11. ↩︎

- IBID ↩︎