Recently a pastor friend of over 20 years sent me a text and asked me what I thought of Amos 3:3. I get this sort of thing a lot, and I have to say I am honored by requests such as this and very much enjoy helping someone to gain a better scriptural understanding of a text. Many are surprised when I tell them that the majority of people that ask me for my take on a particular passage are actually pastors. I appreciate the heartfelt desire of those that ask to best understand a text or what the interpretation of the text means to us. I love the multiplicity of the body’s gifting when crafting a sermon. I used to preach a good deal and would nearly always ask for a panel to work through my sermon with me. Usually, the best part of the message came from something added by the panel. There is wealth in the gifting of the community of Jesus.

People regularly reply to my answers and wonder how I came to this, or how I “got all of that” out of the text. Well, this is a lifetime of understanding (that led to a Th.D.) but let me show you a bit of the process. This is a large part of what we teach at Covenant Theological Seminary.

Exegesis is “the process of careful analytical study of the Bible to produce useful interpretations of those passages.” [1] (In Greek this word “exegesis” is derived from ἐξηγέομαι (exegeomai), which means simply to explain.

For most of our readers that think and primarily communicate in English this is important because the Bible wasn’t written or spoken in our native language. We have to translate the biblical languages and then determine what application it may have to us. The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary states the goal of exegesis is “to know neither less nor more than the information actually contained in the passage. Exegesis … places no premium on speculation or inventiveness” and “novelty in interpretation is not prized.” [2]

Simply put, exegesis is not about discovering what we think a text means (or want it to mean) but what the biblical author meant. It’s concerned with intentionality—what the author intended his original readers to understand. [3]

My good friend and mentor John Walton would say that the Bible was written “for us, but not to us.” This hermeneutic, recently termed “cognitive environment criticism,”[4] is implicit in Walton’s earlier publications, such as Ancient Israelite Literature in its Cultural Context (1989) and The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament (2000). However, the phrase “for us, but not to us” does not appear in print, as far as we can tell, until 2008 when it is found in the final sentence of his article, fittingly titled, “Interpreting the Bible as an Ancient Near Eastern Document” (based on a paper presented in January 2004). The phrase (and several variations) subsequently appears throughout Walton’s Lost World volumes and in his Old Testament Theology for Christians: From Ancient Context to Enduring Belief (2017).

The part of scripture that we need to interpret comes when we understand that the text means what the author intended to interpret. It may or may not have any application to us today.

Unfortunately, most people do not approach scripture this way. Rather, they often read meaning into a text that may or may not be there. This is called eisegesis and is the opposite of exegesis. We see this too often in sermons, someone stating a point they want to make and then trying to use a scripture or verse to prove their point or position. We sometimes refer to this as proof texting.

Proper exegesis requires context. Many have come up with a plan or path to best understand scripture. X44 tends to lean towards a Socio-Rhetorical Interpretation, that is first understanding the textures of a text and its reception. If this is new to you, I would suggest Vernon K. Robbins book “exploring the Texture of Texts: A Guide to Socio-Rhetorical Interpretations.” We have several X44 videos on interpretation.

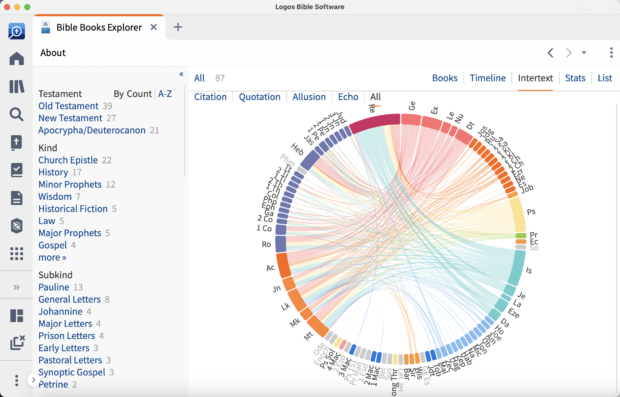

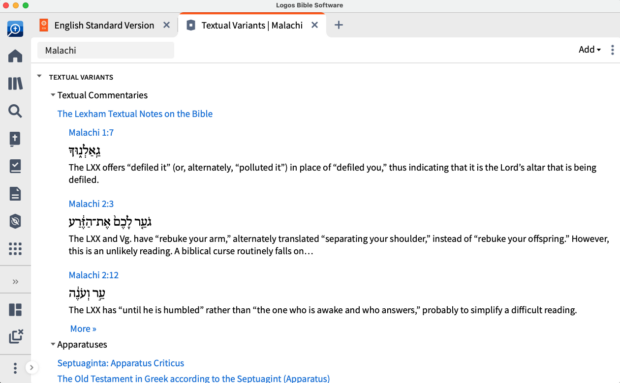

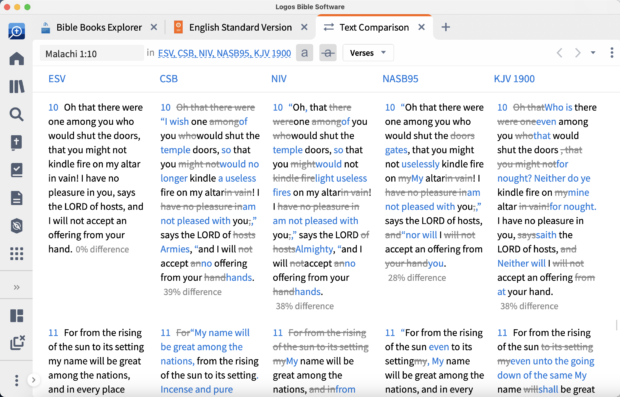

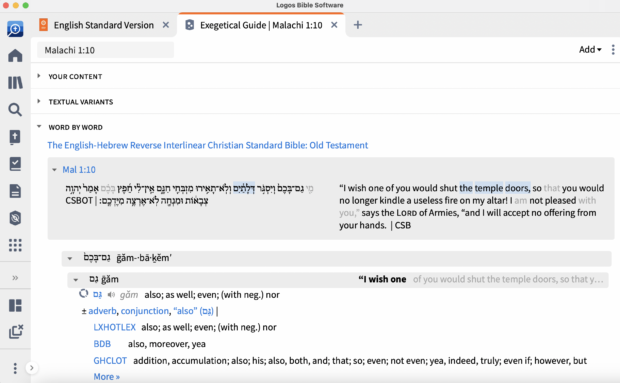

Naselli [5] offers a similar take by considering these 8 steps: (SPECIAL THANKS TO MY FRIENDS AT LOGOS.COM FOR THE VISUALS, whose software I use nearly every hour.) Logos is likely the best exegetical tool, so I am going to demonstrate how I might use it.

1. Genre

Determine the passage’s style of literature. Is it poetry? Historical narrative? An epistle?

2. Textual criticism

Study the manuscript evidence to determine the original text’s exact wording.

3. Translation

Translate the original language and compare other translations. (This is where a good Bible app comes in handy, especially if you do not know biblical Hebrew or Greek. More on that below.)

4. Greek and Hebrew grammar

Consider how sentences communicate by looking into their original language—words, phrases, and clauses.

5. Argument diagram

Trace the author’s logical argument by arcing, bracketing, or phrasing.

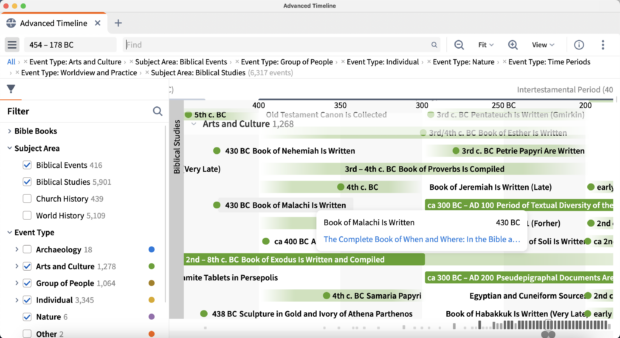

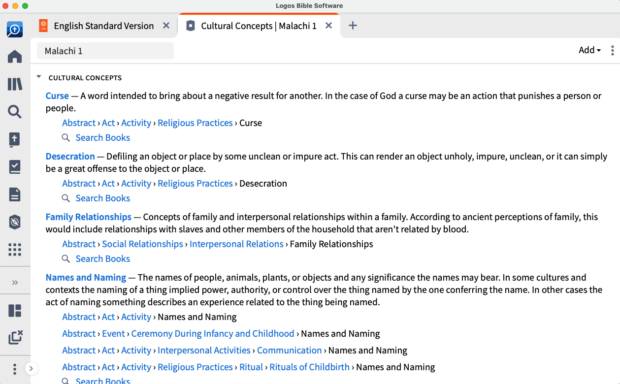

6. Historical-cultural context

Understand the situation in which the author composed the literature and any historical-cultural details that the author mentions or probably assumes.

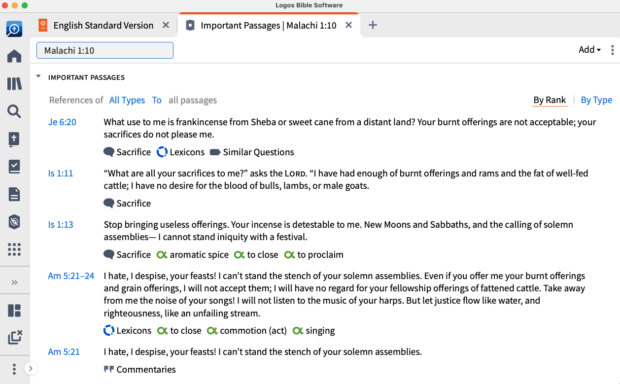

7. Literary context

Understand the role a passage plays in its whole book (and the whole Bible).

8. Word studies

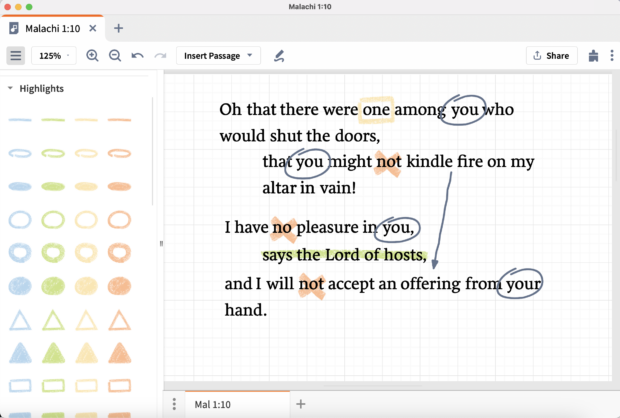

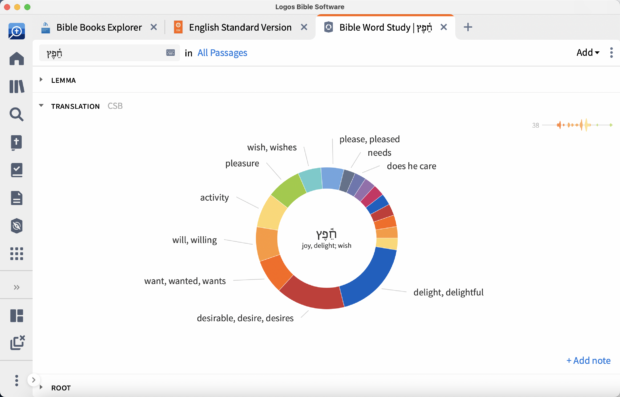

Unpack key words, phrases, and concepts. You can jump into a Bible word study right from your passage. For example, if you noticed that the ESV says “pleasure” and CSB and NIV say “pleased” in step 3, you can take a closer look at the word.

So now that you are beginning to understand how I, or a theologian thinks about scripture, let me give you a hands-on example. The verse my friend asked about specifically was Amos 3:3 so I will use my response to him to demonstrate an exegesis based off of the FREE tools of Bible Hub available on the internet to anyone. I realize Logos is likely more expensive than most people are willing to invest. (But I continually argue that exegesis should be a large part of every Christian’s life.)

Let’s dive into the text! First let’s just consider some simple Observations:

I would suggest just using a browser and type in the verse you wish to know more about followed by the word “interlinear.” This will likely bring up a Bible Hub link.

Hebrew reads right to left so let’s start with the first word. I would recommend clicking the transliterated word itself first, but also clicking the Strong’s number above it to give you a better root word understanding. In this case we see the English “can walk” is from the Hebrew “halak” which is the common word for “to walk.” However, something neither of these software options will tell you plainly is that “halak” became an idiom in Hebrew metaphorically referring to the Edenic walk or relationship of intimacy that we should be desirous of with the Father. Thats where my 25 years of Theology and training may come in helpful. But let’s not jump to conclusions, that may be inferred, or it may not be. Let’s continue.

Two usually means “two” simply or in plain reading, but it is a cardinal number in Hebrew denoting plurality so that can simply mean “more than one” – so here it has to be interpreted in context of the rest of the scripture. (You will find this in Bible Hub reading the commentary section.) So far these aren’t major implications.

Together is a word of being united linguistically both in Hebrew and in our modern English context. NT Greek would be “of one accord” which you may be more familiar with. This is where you might want to stop and think, is there is a slight connection to using the term halak? Maybe, but the text still doesn’t necessarily say that or give us that.

“Except” here in Hebrew functions like a substantive adverb, it is essentially adding “not” in front of something. We do this regularly in English, turning things into the opposite. (Don’t do that.)

In this particular case, we now arrive to why the original person questions the verse, interpretation gets a bit sketchy for scholars here and this comes out in commentary. The issue is in Hebrew the structure gets strange, the word translated as “unless” or something similar is simply “im” in Hebrew which is used over 700 times to simply mean “if;” but can also function like an interrogative participle which in Hebrew would mean it takes on the notion of “although, except, or however.” Lastly, to make it even more complicated, it is also a contronym in Hebrew, so it strangely can also mean sort of the opposite which would be “truly or surely.” This combined with the substantive adverb in front makes any scholar scratch their head.

It continues to be strange with the last singular word in Hebrew is “ya’ad” which they translate “they are agreed” but this is also unique as in Hebrew it functions as the main verb of the sentence. To make it more complicated, the word is only found two places in scripture here and in Psalm 48:4 where it rather takes a notion of assembly rather than agreement, but the root word is a lot more common which usually means appointed. My point is that none of this really helps us much, the truth is it could be interpreted a couple of different ways.

Amos 3:3 is part of a series of cause-and-effect statements to establish Amos’ right and duty to prophesy. The word in 3:3 which must be dealt with is ya’ad (to agree-KJV); it is a Niphal (passive or reflective verb) verb as I alluded to above. All of these things mean something to me, but they likely do not to you. Of course, you can think through it and likely come to a similar thought, that the point of the verse is that Amos would not have been prophesying had God not called him (after all, Amos was neither a prophet nor a son of a prophet) the same as two people would not be walking together unless they had previously made an appointment to meet each other. We could just leave it there, but a good scholar digs deeper. Let’s see what other scholars think and why.

W. J. Deane, The Pulpit Commentary (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1950), Vol. XIV, p. 40 writes:

The contents of these verses are not to be reduced to the general thought, that: a -prophet could no more speak without a divine impulse than any other effect could take place without a cause. There was certainly no need for a long series of examples, such as we have In very. 3-6, to substantiate or illustrate the thought, which a reflecting hearer would hardly have disputed, that there was a connection between cause and effect. The examples are evidently selected with the view of showing that the utterances of the prophet originate with God. This is obvious enough In vers. 7,8. The first clause, ‘Do two men walk together, without having agreed as to their meeting?’ (no’ad, to betake one’s sell to a place, to meet together at an appointed place’or an appointed time; compare Job ii:11, Josh. xi.5, Neh. vi.2; not merely to agree together) contains something more than the trivial truth, that two persons do not take a walk, together without a previous arrangement. The two who walk together are Jehovah and the prophet (Cyril); not Jehovah and the nation, to which the judgment is predicted. . . . Amos went as prophet to Samaria or Bethel, because the Lord had sent him thither to preach judgment on the sinful kingdom.”

Carl Friedrich Keil, The Twelve Minor Prophets (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1951), p. 260 says:

“The ‘two’ are God’s judgments and the prophet’s word. These do not coincide by mere chance, no more than two persons pursue in company the same end without previous agreement. The prophet announces God’s judgment because God has commissioned him; the prophet Is of one mind with God, therefore the Lord is with him and confirms his words.

I also came across an interesting article when researching that shows Leroy Garrett making a claim that this verse represents a biblical reasoning for “unity in diversity”. I don’t see that in the exegesis above.

So, let’s get back to where we started. What did this text mean to the intended audience? I think we need to let this passage mostly represent its intended audience. Personally, I’m not sure there’s much if any application to us here today, but that’s just me! I think we need to let the primary message to the intended audience be the primary message in most cases. But perhaps there is a takeaway for us, that is what everyone is looking for right? Let’s consider that.

If this text in Amos supports anything remotely connected to present-day relationships, the context would show us it would be the necessity of agreeing to meet with a brother/sister in order to walk in unity. In the first century and before most “church” settings were small; there really isn’t a context for the mega church setting we are most all in today. Most situations either address a small intimate group described as a family (which meant those in your circle more than blood relation) or it mean communal Israel. Biblical diversity can be beautiful, but it can also cause us to be “out of harmony.” In a bigger picture, we do not have to agree on everything in order to walk together, even though as Christians we will agree on many things and certainly on the authority of Scripture to take us further in our understanding of God’s truth.

This is where things often get miscommunicated, because as brothers and sisters in Christ, we are in a covenant together “walking” as in the garden might apply to our most intimate relationships, spouses, family, and perhaps our inner circle; but this verse seems to better point towards communal unity in Israel, the big church. And let’s not forget that when Amos was penned, Israel was totally messed up and a far cry from Eden. Thats should adjust your application to your situation.

But I don’t think anyone will argue that we need to be in agreement with God or moving in that direction without imagining that we have arrived at a point where we can demand agreement from others with us. We may not agree on some things that are peripheral to maintaining and manifesting the biblical unity that exists in Christ. If you “swim” in a tribe of other intimate relational covenant fish you’re going to be in a better place each day.

Yet one thing I think this verse shows us that is timeless is that we should understand that a disagreeing brother/sister should not automatically be equated with a disobedient brother/sister. It is far too facile to label disagreement as disobedience and I think this has had devastating consequences on our church.

When anyone starts to think that God’s way is their way and if someone disagrees with them than they disagree with God; they open up a contentious entanglement with the world.

Can we agree to disagree and yet agree to walk together in some measure in the work of God and in the enjoyment of fellowship or at least rejoice at what God is doing in the lives and ministries of others without becoming their theological critics? On the other hand, let’s discuss it in love! Let’s return to the hillside meetings of the first century searching for truth for most of our day.

One true measure of our spiritual maturity and fruit may be whether we will agree to walk together in true obedience and genuine fellowship in spite of our disagreements. Exegesis should come as a circular result of searching for what God has for you and those in your sphere, as God’s word is revealed and applied.

- Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, “Exegesis” (Yale University Press, New Haven, CT), 1992.

- Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, “Exegesis” (Yale University Press, New Haven, CT), 1992.

- D. Fee, Handbook to New Testament Exegesis (1993), 27.

- Walton, Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament (second edition, 2018), 11, 18; Walton, Old Testament Theology for Christians, 16.

- Naselli, Andy. New Testament Exegesis: Understanding and Applying the New Testament (Course), (Lexham Press, Bellingham, WA), 2016